It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing.

![]()

On 06/28/10, the Supreme Court of the United States decided Bilski v. Kappos, a case about what subject matter (including software and business method patents) is eligible for patent protection under US law.

Unfortunately, the Supremes blew it. Here’s why. Bear with me, this will take some time to explain.

Table Of Contents

I. Separation Of Powers – Who Does What In The US Government

II. Patent Law In Practice

III. A Brief History Of Patent Law

A. The Constitution

B. The Patent Act

0. Definitions, 35 U.S.C. §100, 35 U.S.C. §273(a)(3).

1. Subject Matter, 35 U.S.C. §101.

2. Novelty (statutory bars), 35 U.S.C. §102.

3. Utility, 35 U.S.C. §101, 35 U.S.C. §112 (first paragraph).

4. Nonobviousness, 35 U.S.C. §103.

5. Specification (written description, enablement, best mode), 35 U.S.C. §112 (first paragraph).

IV. Patent Law: What It Says vs. What It Means

A. What Patent Law Says

B. The Supreme Court’s Pre-CAFC §101 Trilogy

C. CAFC Created; Fewer Supreme Court Patent Cases Heard

D. CAFC: Alappat, State Street, Reaction By Congress

E. CAFC: Bilski

V. The Supreme Court Bilski Case

A. Kennedy’s “Majority” Opinion

B. Stevens’s Concurring Opinion

C. Breyer’s Concurring Opinion

D. Summary: You may ask yourself, where does that highway lead to?

Appendix A – Related Patent Commentary by Erik J. Heels

Appendix B – Third-Party Commentary On Bilski

Appendix C – Patent Law Chronology

1. 1952 Patent Act (Congress).

2. 1972, Benson (US Supreme Court) (“§101 Trilogy” 1 of 3). Laws of Nature, natural/physical phenomena, and Abstract Ideas Fail §101.

3. 1978, Flook (US Supreme Court) (“§101 Trilogy” 2 of 3).

4. 1980, Chakrabarty (US Supreme Court).

5. 1981, Diehr (US Supreme Court) (“§101 Trilogy” 3 of 3).

6. 1982, CAFC Formed.

7. 1994, Alappat (CAFC).

8. 1998, State Street (CAFC) – Useful, Concrete, and Tangible Result.

9. 2010, Bilski (US Supreme Court).

I. Separation Of Powers – Who Does What In The US Government

There are three branches of government in the United States. Each branch has a defined role. Two of the three branches are supposed to be able to overrule the other so that no one branch has absolute power. All of this was decided by the people in the form of the US Constitution.

- The Legislative branch (the Senate and the House of Representatives, collectively and informally called Congress) writes the laws.

- The Executive branch (the President and agencies such as the Department of Commerce) executes the law.

- The Judicial branch (trial courts, appeals courts, and the Supreme Court) explains the laws.

To paraphrase what the late great Professor David Gregory said:

“[W]hat the state courts say is not the law. What the circuit courts say is not the law. And what the dissenting Supreme Court opinions say is not the law. The only thing that is the law is what the majority of the Supreme Court says is the law. And so the best way to truly learn the law is to read the major Supreme Court decisions about the law, to read only the majority opinions, and to read all of them.”

I am reminded of a political cartoon from the 1980s showing a king shouting from a balcony to his rioting subjects below: “You have to do what I say or I can’t be king anymore!” Exactly.

- Writing laws is easy.

- Executing laws is easy.

- Explaining laws is hard. As the only unelected branch of government, the judicial branch derives its legitimacy and authority from and in proportion to its ability to do its job well, to explain the law.

The Supreme Court must explain the law or it is not the supreme court anymore.

II. Patent Law In Practice

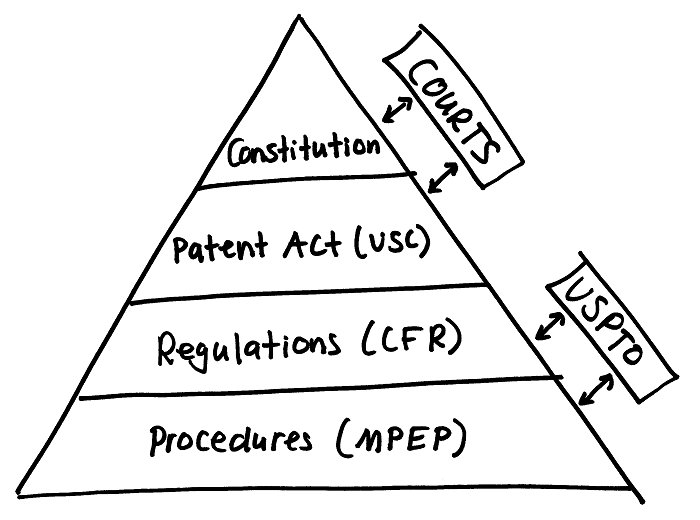

The following drawing and explanation are excerpted from my Drawing That Explains Patent Laws article.

At the top of the pyramid is the United States Constitution. Article 1 Section 8 of the Constitution says:

“The Congress shall have Power … To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries;”

So patent rights and copyright rights come from the same clause in the Constitution. Oddly, the Constitution says nothing about trademark rights. And in our government, the Patent Office and the Trademark Office are combined (in the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO)), but the Copyright Office is separate. So Congress doesn’t always do things the way the drafters of the Constitution thought that they would.

Next in the pyramid (working top to bottom) is the Patent Act. When our lawmakers in Congress (the Senate and the House of Representatives) want to make a new law, they write it, debate on it, and, if they agree on it, then the new law becomes part of the United States Code. The United States Code is divided into smaller pieces called titles, parts, chapters, and sections. The Patent Act is the short name for our patent laws, which exist in Title 35 of the United States Code (35 USC for short). The version of the Patent Act that I use is about 88 pages long.

Next in the pyramid is the Patent Rules (also called patent regulations). Congress writes the laws, but different agencies of the government have to carry out those laws. The Federal Rules are the rules that the agencies write to help explain the laws and how they’ll be carried out. For patent laws, the USPTO writes the Patent Rules, and those appear in Title 37 of the Code of Federal Regulations (37 CFR for short). The version of the Patent Rules that I use is about 336 pages long.

The bottom of the pyramid is the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP). The MPEP was written by the USPTO for patent examiners to help them do their jobs. Most patent examiners are not lawyers. So the MPEP is designed to help them understand and apply patent law (the Constitution, the Patent Act, and the Patent Rules). The MPEP is the most frequently used reference book for patent examiners. So it is helpful for patent lawyers like me to know the MPEP. The version of the MPEP that I use is about 3000 pages long.

So we’ve gone from one sentence (Constitution) to 88 pages (Patent Act) to 336 pages (Patent Rules) to 3000 pages (MPEP).

The fun part about the patent laws is that they are constantly changing. The job of the courts (and ultimately the Supreme Court) is to determine what the law is – what it means. So whenever there is a patent dispute that ends up in court, the courts will be interpreting what the patent laws (the Constitution and the Patent Act) mean. Congress can also change the Patent Act, but that is harder to do. And the people of the United States can change the Constitution, but that is even harder to do.

At the same time, the USPTO is constantly revising the Patent Rules and the MPEP. And sometimes the way the USPTO thinks the patent laws should be applied differs from how the courts think the patent laws should be applied.

III. A Brief History Of Patent Law

A. The Constitution

Keep in mind the above drawing. The Constitution says that:

“The Congress shall have Power … To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries;”

B. The Patent Act

Here are the key sections of the Patent Act, two sections of definitions, 5 basic requirements for patentability:

0. Definitions, 35 U.S.C. §100, 35 U.S.C. §273(a)(3).

Note the circular definition of “process.”

35 U.S.C. 100 Definitions.

When used in this title unless the context otherwise indicates –

(a) The term “invention” means invention or discovery.

(b) The term “process” means process, art, or method, and includes a new use of a known process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter, or material.

Note the definition of “method” for defenses to infringement.

35 U.S.C. 273. Defense to infringement based on earlier inventor.

(a) DEFINITIONS. For purposes of this section– …

(3) the term “method” means a method of doing or conducting business…

(Added Nov. 29, 1999, Public Law 106-113, sec. 1000(a)(9), 113 Stat. 1501A-555 (S. 1948 sec. 4302).)

See:

http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/documents/appxl_35_U_S_C_100.htm

http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/documents/appxl_35_U_S_C_273.htm

1. Subject Matter, 35 U.S.C. §101.

35 U.S.C. 101 Inventions patentable.

Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.

See:

http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/documents/0700_706_03_a.htm

http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/documents/2100_2106.htm

2. Novelty (statutory bars), 35 U.S.C. §102.

35 U.S.C. 102 Conditions for patentability; novelty and loss of right to patent.

A person shall be entitled to a patent unless —

(a) the invention was known or used by others in this country, or patented or described in a printed publication in this or a foreign country, before the invention thereof by the applicant for patent, or

(b) the invention was patented or described in a printed publication in this or a foreign country or in public use or on sale in this country, more than one year prior to the date of the application for patent in the United States…

See:

http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/documents/appxl_35_U_S_C_102.htm

3. Utility, 35 U.S.C. §101, 35 U.S.C. §112 (first paragraph).

The term “useful” appears in 35 35 U.S.C. §101 and “use” appears in 35 U.S.C. §112.

See:

http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/documents/2100_2107.htm

4. Nonobviousness, 35 U.S.C. §103.

35 U.S.C. 103 Conditions for patentability; non-obvious subject matter.

(a) A patent may not be obtained though the invention is not identically disclosed or described as set forth in section 102 of this title, if the differences between the subject matter sought to be patented and the prior art are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which said subject matter pertains….

See:

http://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/documents/2100_2141.htm

5. Specification (written description, enablement, best mode), 35 U.S.C. §112 (first paragraph).

35 U.S.C. 112 Specification.

The specification shall contain a written description of the invention, and of the manner and process of making and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art to which it pertains, or with which it is most nearly connected, to make and use the same, and shall set forth the best mode contemplated by the inventor of carrying out his invention.

IV. Patent Law: What It Says vs. What It Means

A. What Patent Law Says

The legal meaning of words in laws frequently differs from the literal meaning. This problem is compounded by the fact that language itself evolves. That’s why we have courts: to explain what the law means.

The Constitution places no limitations on what “Discoveries” may be entitled to patents.

The current Patent Act was enacted in 1952. The Patent Act enumerates broad categories of inventions/discoveries that may be patentable, including “process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter” (35 U.S.C. §101) where “process” is further (circularly) defined as “process, art, or method” (35 U.S.C. §100), which leaves us with the following patentable subject matter:

- process, art, or method

- machine

- manufacture

- composition of matter

As you can probably guess, “art” in this context does not mean “works of visual art” such as paintings and sculptures. Similarly, “process” and “method” do not mean what mere mortals think they mean.

Explain to us, o courts of law, what these terms mean.

B. The Supreme Court’s Pre-CAFC §101 Trilogy

Between 1972 and 1981, the Supreme Court issued a trilogy of cases on computer-related subject matter patentability (Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63 (1972), Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584 (1978), Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175 (1981)), concluding that 35 U.S.C. §101 should be interpreted broadly and does not exclude computer-related inventions. A fourth case (Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303, 309 (1980)) also addressed subject matter patentability. Taken as a whole, these four cases created three exceptions to the broad categories of patentable subject matter outlined in 35 U.S.C. §101. Namely, according to the Supreme Court, even though 35 U.S.C. §101 does not explicitly say so, the following categories are not patentable subject matter:

- laws of nature

- natural/physical phenomena

- abstract ideas

These judicially-created exceptions to 35 U.S.C. §101 would come back to haunt the Supreme Court in its 2010 Bilski decision. More on this below.

C. CAFC Created; Fewer Supreme Court Patent Cases Heard

In 1982, Congress created the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (CAFC). Unlike the other federal circuit courts (1st Circuit through 11th Circuit), the CAFC’s jurisdiction is based on subject matter (including patents) rather than geography. So while the CAFC’s creation eliminated any issue of conflicting opinions between the various federal circuit courts on patent-related cases, it also reduced the necessity of having any such conflicting circuit court cases appealed to the Supreme Court. As a result, the Supreme Court has had fewer opportunities to rule on patent law post-CAFC.

Which is why every single patent law case that the Supreme Court does rule on is supremely important.

D. CAFC: Alappat, State Street, Reaction By Congress

In 1994, the CAFC restated the Benson-Flook-Diehr (Supreme Court §101 trilogy) rule that (1) laws of nature, (2) natural/physical phenomena, and (3) abstract ideas are not patentable subject matter. In re Alappat, 33 F.3d 1526 (Fed. Cir. 1994).

In 1998 the CAFC ruled (in a nine-page decision by 94-year-old Judge Giles Sutherland Rich) that a computerized business-related patent was valid and specifically rejected the “so-called ‘business method’ exception to statutory subject matter.” State Street Bank & Trust Co. v. Signature Financial Group Inc., 149 F. 3d 1368 (Fed. Cir. 1998). The CAFC restated the Supreme Court rule that abstract ideas are not patentable subject matter and stated that it had previously held that “mathematical algorithms are not patentable subject matter to the extent that they are merely abstract ideas.” At this point, the State Street court was not necessarily trying to make new law. But in continuing to explain how the subject matter of the patent at issue was patentable and distinguishable from “abstract ideas,” the State Street court (perhaps inadvertently) created an exception to the previous judicially-created exceptions, ruling that “to be patentable an algorithm must be applied in a ‘useful’ way,” and that “the transformation of data, representing discrete dollar amounts, by a machine through a series of mathematical calculations into a final share price, constitutes a practical application of a mathematical algorithm, formula, or calculation, because it produces ‘a useful, concrete and tangible result‘ – a final share price momentarily fixed for recording and reporting purposes and even accepted and relied upon by regulatory authorities and in subsequent trades.” (Emphasis added.)

The State Street case has been interpreted to stand for the notion that business methods are patentable. From the table below, you can see why it lends itself to this interpretation, even though the subject matter at issue in State Street was a computerized invention that was ruled to be a machine.

For those of you scoring at home, in 1998, we had:

(35 U.S.C. §101) |

(Exceptions Created By The Supreme Court) |

|

|

In 1999, in response to the CAFC’s controversial State Street decision, Congress amended the Patent Act by passing the American Inventors Protection Act (commonly referred to as the First Inventor Defense Act) to provide a defense to those sued for infringing business method patents. See 35 U.S.C. §273(a)(3) above.

E. CAFC: Bilski

In 2008, the CAFC issued a decision (nine to three in 132 pages of concurring and dissenting opinions; Chief Judge Michel wrote the majority opinion) that interpreted the Supreme Court’s Benson case and other Supreme Court cases to mean that a claimed process is patent-eligible under 35 U.S.C. §101 only if (1) it is tied to a particular machine or apparatus, or (2) it transforms a particular article into a different state or thing. In re Bilski, 545 F. 3d 943 (Fed. Cir. 2008). This so-called “machine-or-transformation” test was used to uphold the rejection of Bilski’s patent application, which had previously been rejected by both the USPTO examiner and the USPTO Board of Patent Appeals and Interferences (BPAI). The CAFC Bilski majority specifically rejected the State Street “useful, concrete and tangible result” test in favor of the “machine-or-transformation” test.

In a concurring opinion, Judges Dyk and Linn reviewed the history of the 1793 Patent Act and the 1952 Patent Act to support the conclusion that Bilski’s claim did not recite patentable subject matter.

In a (scathing and well-reasoned) dissenting opinion, Judge Newman wrote that:

- the Bilski patent application had never been properly examined under non-§101 criteria (including the requirements of novelly, non-obviousness, utility, and Section 112);

- the Patent Act places no restrictions on the terms “process, art, or method;”

- the majority’s decision conflicts with the Supreme Court’s §101 trilogy and CAFC precedent;

- the majority’s citations of Supreme Court cases are dicta or taken out of context (what Newman called “the strained new reading of Supreme Court quotations”);

- the majority and concurrence use undefined and vague terms (including “business method” and “organizing human activity”); and

- the court’s decision “usurps the legislative role.”

In a dissenting opinion, Judge Mayer wrote that State Street should be overturned because business method patents do not promote the “useful arts” (citing the Constitution).

In a dissenting opinion, Judge Rader wrote that the Bilski patent should have been rejected as being an “abstract idea” (citing the Supreme Court’s §101 trilogy).

For those of you scoring at home, in 2008, we had:

(35 U.S.C. §101) |

(Exceptions Created By The Supreme Court) |

|

|

Bilski appealed to the Supreme Court.

V. The Supreme Court Bilski Case

The CAFC Bilski decision was appealed, and the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. There were 78 amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefs (dated 01/28/09 – 10/02/09) filed with the court for the two questions presented:

“[1. ] Whether the Federal Circuit erred by holding that a ‘process’ must be tied to a particular machine or apparatus, or transform a particular article into a different state or thing (‘machine-or-transformation’ test), to be eligible for patenting under 35 U.S.C. §101, despite this Court’s precedent declining to limit the broad statutory grant of patent eligibility for ‘any’ new and useful process beyond excluding patents for ‘laws of nature, [natural/]physical phenomena, and abstract ideas.’

[2. ] Whether the Federal Circuit’s ‘machine-or-transformation’ test for patent eligibility, which effectively forecloses meaningful patent protection to many business methods, contradicts the clear Congressional intent that patents protect ‘method[s] of doing or conducting business.’ 35 U.S.C. §273.”

On 06/28/10, the Supreme Court ruled (in 71 pages of concurring and dissenting opinions), answering both of the questions above in the affirmative.

A. Kennedy’s “Majority” Opinion

Justice Kennedy wrote the 16-page majority opinion, which was joined by Justices Roberts, Thomas, Alito, and Scalia (except that Justice Scalia did not join parts II-B-2 and II-C-2).

Justices Stevens, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor wrote a 47-page concurring opinion.

Justice Breyer and Scalia wrote a 4-page concurring opinion.

So that’s 4.5 justices for the Kennedy “majority,” 3.5 for the Stevens concurrence, and 1.0 for the Breyer concurrence (since Bryer joined the Stevens concurrence and Scalia joined the Kennedy opinion in part). Hurray for clarity.

Kennedy’s opinion starts by framing the question oddly as “whether a patent can be issued for a claimed invention designed for the business world.” It seems to me that this it a simple question to answer: yes. He continues by omitting the preamble from the cited Claim 1, thus depriving the claim of its proper context. (Compare this to how Judge Rich cited the claim at issue in the State Street case.)

Kennedy then reviews the Supreme Court’s §101 trilogy and concludes that the judicially created exceptions to 35 U.S.C. §101 are consistent with the notion that a patentable process must be “new and useful.” While 35 U.S.C. §101 does include the words “new and useful,” the concepts of “novelty” and “usefulness” are defined elsewhere in the Patent Act, namely 35 U.S.C §102 (novelty) and 35 U.S.C. §112 (utility). A well-reasoned §101 determination should not be made based on terms primarily defined elsewhere in the Patent Act.

In Section II-B-1, Kennedy tries to explain the Court’s unwillingness to create new judicially-created exceptions to patently subject matter despite the fact that its trilogy of §101 cases created three such exceptions (namely, laws of nature, natural/physical phenomena, and abstract ideas). This is a big hurdle to overcome. Respondent (Kappos) and various amicus brief writers would have the Supreme Court carve out new exceptions for software patents, business method patents, or both. Kennendy’s response? “This court has not indicated that the existence of these well-established exceptions gives the Judiciary the carte blanche to impose other limitations that are inconsistent with the text and the statute’s purpose and design.”

I have a better idea. Throw out all of the judicially-created §101 exceptions. Because §101 is, and always has been, a red herring. I have not yet met a patent claim for a law if nature, a natural/physical phenomenon, or an abstract idea that would pass scrutiny under the Patent Act’s requirements of novelty, utility, and non-obviousness. Gravity? Not new. E = mc2? Not new. Bilski’s hedging? Obvious. And so on.

Kennedy then states that “[t]he machine-or-transformation test is not the sole test for deciding whether an invention is a patent-eligible ‘process.'” In other words, if a claimed invention passes the machine-or-transformation test, then it is patent-eligible under §101, but if it fails the machine-or-transformation test, then that is not the end of the §101 inquiry.

Kennedy discusses software patents in Section II-B-2, which is not joined by Scalia. With only four justices concurring on this section, the court’s musings on software patents are, effectively, dicta. Kennedy states that “the machine-or-transformation test would create uncertainly as to the patentability of software…” and that “the Court today is not commenting on the patentability of any particular invention, let alone holding that any … technologies from the Information Age should or should not receive protection.” In other words, a minority of the Justices are not saying that software is or is not patentable. This section concludes with what I like to call the “good luck to you all” clause: “[T]he patent law faces a great challenge in striking the balance between protecting inventors and not granting monopolies over procedures that others would discover by independent, creative application of general principles.” Translation: patent law is challenging, but we the Court choose not to give y’all the guidance you are desperately seeking.

Kennedy’s weakest argument appears in Section II-C-1, where he states that since Congress included the phrase “method of doing or conducting business” in 35 U.S.C. §273(a)(3), then “the statute itself acknowledges that there may be business method patents.” But this simply ignores that 35 U.S.C. §273(a)(3) was enacted by Congress in response to the CAFC’s controversial State Street decision in order to give business owners a we-invented-it-first defense if they were sued for infringing a business method patent. A repudiation of State Street by Congress is not an endorsement of business method patents. A better line of reasoning would have been to state that 35 U.S.C. §101 includes the word “method,” that “business method” is poorly defined, and that §101 should be read broadly. (Besides, §101 is a red herring. And most so-called “business method” patent applications would fail the separate statutory requirements of novelty, utility, and non-obviousness. But I digress.)

Then, Kennedy either confuses §101 with §102, §103, and §112 or acknowledges that §101 is a red herring: “Finally, even if a particular business method fits into the statutory definition of a ‘process,’ that does not mean that the method should be granted. In order to receive patent protection, any claimed invention must be novel, §101, nonobvious, §103, and fully and particularly described, §112.” So close to reason, yet so far.

In Section III, Kennedy concludes that Bilski’s claimed invention is an “abstract idea” without providing any support for this conclusion. I don’t know a single patent agent or attorney who was not taught to claim inventions with specifically defined language. Bilski’s U.S. Patent Application Serial No. 08/833,892, claim 1, states:

“managing the consumption risk costs of a commodity sold by a commodity provider at a fixed price,” and consists of the following steps:

“(a) initiating a series of transactions between said commodity provider and consumers of said commodity wherein said consumers purchase said commodity at a fixed rate based upon historical averages, said fixed rate corresponding to a risk position of said consumers;

(b) identifying market participants for said commodity having a counter-risk position to said consumers; and

(c) initiating a series of transactions between said commodity provider and said market participants at a second fixed rate such that said series of market participant transactions balances the risk position of said series of consumer transactions.”

Which part of claim 1 is the “abstract idea” part? If Kennedy is hanging his hat on this peg, then he should have pointed this out. And if this claim is inadequate, then shouldn’t that be addressed under §112 or other provisions of the Patent Act?

Kennedy’s opinion concludes by punting §101 jurisprudence back to the CAFC: “In disapproving an exclusive machine-or-transformation test, we by no means foreclose the Federal Circuit’s development of other limiting criteria that further the purposes of the Patent Act and are not inconsistent with its text.”

B. Stevens’s Concurring Opinion

Stevens writes that it would have been wiser for the Court to hold that Bilski’s claim was not patentable because “it describes only a general method of engaging in business transactions — and business methods are not patentable … ‘process[es]’ under §101.”

Stevens relies heavily on Judges Dyk’s concurring opinion in the CAFC’s Bilski decision. But that decision, as pointed out by the (better reasoned) dissenting opinion of Judge Newman, presents a selective history of U.S. and English patent law that is both out of context and inapplicable (since the patent laws of the new United States were already diverging from English common law when the 1793 Patent Act was enacted).

In Section II, Stevens generously refers to the Court’s opinion as “less than pellucid in more than one respect…” On this point, I agree. Stevens correctly points out that specificity objections should be raised under §112 and novelty under §102. In his most well-reasoned argument, he states: “The Court essentially asserts its conclusion that petitioner’s application claims an abstract idea. This mode of analysis (or lack thereof) may have led to the correct outcome in this case, but it also means that the Court’s musings on this issue stand for very little.” In other words, assertion is a poor substitute for reasoned analysis. Unfortunately, in footnote 9, Stevens makes the same assersion-ain’t-analysis mistake that he criticizes the majority for making when he states that “many processes that would make for absurd patents are not abstract ideas. Nor can the requirements of novelty, nonobviousness, and particular description pick up the slack.” Really? Why not. I think that novelty, nonobviousness, and particular description can pick up the slack and that §101 is a red herring.

Stevens goes off on a tangent, criticizing imagined patents on “training a dog” (for example) while ignoring the fact that passing a §101 test is only one step towards getting a patent granted. The Court loses credibility when it criticizes any particular subject matter as “absurd” or “comical.” One man’s junk is another’s fortune. And besides, novelty, nonobviousness, and particular description can pick up the slack.

Regarding the lack of a historical basis for business method patents, Steven cites a 1778 business method patent, which actually supports the opposite conclusion.

The strongest argument made by Stevens appears in Section V and counters the weakest argument made by Kennedy, namely that the 1999 enactment of the American Inventors Protection Act by Congress in response to the CAFC’s State Street decision cannot logically be viewed as an endorsement of business method patents. This section is an example of strong reasoning:

If, tomorrow, Congress were to conclude that patents on business methods are so important that the special infringement defense in Sec. 273 ought to be abolished, and thus repealed that provision, this could paradoxically strengthen the case against such patents because there would no longer be a Sec. 273 that ‘acknowledges … business method patents,’ [citation omitted]. That is not a sound method of statutory interpretation.

In the so-close-but-so-far category, Stevens then writes: “Section 273 is a red herring; we should be focusing our attention on §101 itself.” But §101 is also a red herring.

Stevens later asserts that “patents on methods of conducting business generally are composed largely or entirely of intangible steps.” Really? I’ve never seen an issued patent claim containing a single intangible step.

C. Breyer’s Concurring Opinion

Breyer agrees with Stevens that a “business method” is not a “method” under 35 U.S.C. §101. Bryer wrote separately to highlight the points on which the court “agrees” (since the other 67 pages of opinion do a poor job of this).

First, that §101 is not limited. My response: we already knew this from the judicially-created exceptions (laws of nature, natural/physical phenomena, abstract ideas).

Second, that “[t]transformation and reduction of an article to a different state or thing is the clue to the patentability of a process claim that does not include particular machines.” Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U. S. 175, 184 (emphasis added; internal quotation marks omitted). My response: this “the clue” language must be put in context of the trilogy. The Supreme Court explicitly declined to “hold that no process patent could ever qualify if it did not meet [machine or transformation] requirements.” Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63, 71. Flook took a similar approach, “assum[ing] that a valid process patent may issue even if it does not meet [the machine-or-transformation test].” 437 U.S., at 588, n. 9. (See Kennedy’s majority opinion pp 7-8.)

Third, the machine-or-transformation test has never been the sole test for determining patentability. My response: agreed. There’s also §102, §103, §112.

Fourth, “[t]o the extent that the Federal Circuit’s decision in this case rejected [the State Street ‘useful, concrete, and tangible result’] approach, nothing in today’s decision should be taken of disapproving of that determination. Translation: In other words, we the Supreme Court were not asked to overrule State Street but would love to do so.

D. Summary: You may ask yourself, where does that highway lead to?

For those of you scoring at home, in 2010, we have:

(35 U.S.C. §101) |

(Exceptions Created By The Supreme Court) |

|

|

In other words, 2010 looks a lot like 1982.

In short, the Supreme Court ruled in Bilski that the CAFC erred by holding that a “process” must be tied to a particular machine or apparatus, or transform a particular article into a different state or thing (‘machine-or-transformation’ test), to be eligible for patenting under 35 U.S.C. §101, because the Supreme Court’s precedent has declined to limit the broad statutory grant of patent eligibility for any new and useful process beyond excluding patents for “laws of nature, natural/physical phenomena, and abstract ideas.”

In so doing, the Supreme Court failed to define a new §101 test and failed to define key terms (including “abstract idea,” “software patent,” and “business method”) upon which it bases its decision.

The worst part of Bilski is that no single decision is consistently well-reasoned. The judicial branch is the only branch which must explain its actions, and it derives its authority from and in proportion to its ability to do so. A weak decision like Bilski weakens the Court. The patent community waited nearly a year and a half for this decision yet did not get the certainly, reasoning, and guidance that it deserves. We waited for answers, we got nothing but questions.

As a practitioner, I do not now look to the 2010 Supreme Court for patent law guidance. I do not look to the CAFC. I look instead to the 1982 Supreme Court.

Paraphrasing William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, Bilski is a tale full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

Besides, §101 is a red herring.

Appendix A – Related Patent Commentary by Erik J. Heels

- Stop Wasting Money On Patents

Patent Law Is Broken - LawLawLaw 2009-01-29

Apple vs. Google, Bilski, Recession Ending? - LawLawLaw 2009-10-17

Technology, Law, Baseball, Rock ‘n’ Roll, Etc. - LawLawLaw 2008-11-24

Technology, Law, Baseball, Rock ‘n’ Roll, Etc. - Reinventing Patent Law

Death, taxes, and uncertain patent laws. - Patent Reform Turns Patent Attorneys Into Patent Pending Attorneys

Expect to pay more for, wait longer for, and get less from your patent application. - Drawing That Explains Patent Laws

From Chief Justice to the patent examiner. - Easy To Infringe

Draft to the rule, don’t draft to the exception. - How To Get And Defend A Patent Without Going Broke

It is possible for independent inventors and small businesses to acquire patents and protect their ideas without going broke in the process. - Software Patents: Good Or Evil? (Part 1)

From the fourth annual Law and Technology Conference at the Technology Law Center of the University of Maine School of Law. - Patents vs. Trade Secrets

The advantages and disadvantages of protecting business ideas with patents and trade secrets.

Appendix B – Third-Party Commentary On Bilski

- Supreme Court Rules Narrowly In Bilski; Business Method & Software Patents Survive from Techdirt by Mike Masnick

- Second Thoughts On Bilski: Could Another Case Get A Direct Ruling On Business Method Patentability? from Techdirt by Mike Masnick

- Supreme Court: Software is Patentable… Sometimes from ReadWriteWeb by Mike Melanson

- Bilski v. Kappos from Patently-O by Dennis Crouch

- Bilski v. Kappos and the Anti-State-Street-Majority from Patently-O by Dennis Crouch

- The Supreme Court Punts On Business Method Patents from TechCrunch by Erick Schonfeld

- Supreme Court Ruling Leaves Future of Software Patents in Limbo from Mashable! by Christina Warren

- Guest Post: Why Bilski Benefits Startup Companies from Patently-O by Ted Sichelman

- Guest Post on Bilski: Throwing Back the Gauntlet from Patently-O Shubha Ghosh

- Bilski v. Kappos: The Supreme Court Declines to Prohibit Business Method Patents from EFF.org Updates by Michael Barclay

- It’s Time To Get Rid Of Business Method Patents from Silicon Alley Insider by Fred Wilson

- Bummed Out About Bilski from Feld Thoughts by Brad Feld

- Sawyer on Why Bilski Really Means That Software Companies Should Leave the US from Feld Thoughts by Brad Feld

Appendix C – Patent Law Chronology

Except where stated otherwise, the text below is excerpted from the USPTO’s 10/16/05 and 11/22/05 subject matter patentability (35 U.S.C. §101) guidelines.

1. 1952 Patent Act (Congress).

————————————————————

“Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title.” 35 U.S.C. §101.

“The term ‘process’ means process, art, or method, and includes a new use of a known process, machine, manufacture, composition of matter, or material.” 35 U.S.C. §100(b).

2. 1972, Benson (US Supreme Court) (“§101 Trilogy” 1 of 3). Laws of Nature, natural/physical phenomena, and Abstract Ideas Fail §101.

————————————————————

One may not patent every “substantial practical application” of an idea, law of nature or natural/physical phenomena because such a patent “in practical effect be a patent on the [idea, law of nature or natural/physical phenomena] itself.” Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63, 71-72, 175 USPQ 673, 676 (1972) (finding a machine-implemented method of converting binary-coded decimal numbers into pure binary numbers unpatentable).

Thus, a claim that recites a computer that solely calculates a mathematical formula (see Benson), a computer disk that solely stores a mathematical formula, or a electromagnetic carrier signal that carries solely a mathematical formula is not statutory.

3. 1978, Flook (US Supreme Court) (“§101 Trilogy” 2 of 3).

————————————————————

Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584, 589, 198 USPQ 193, 197 (1978).

4. 1980, Chakrabarty (US Supreme Court).

————————————————————

Thus, “a new mineral discovered in the earth or a new plant found in the wild is not patentable subject matter” under Section 101. Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303, 309 (1980), 206 USPQ at 197.

5. 1981, Diehr (US Supreme Court) (“§101 Trilogy” 3 of 3).

————————————————————

“In determining the eligibility of respondents’ claimed process for patent protection under §101, their claims must be considered as a whole. It is inappropriate to dissect the claims into old and new elements and then to ignore the presence of the old elements in the analysis. This is particularly true in a process claim because a new combination of steps in a process may be patentable even though all the constituents of the combination were well known and in common use before the combination was made.” Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175, 188-89, 209 USPQ 1, 9 (1981).

“It is now commonplace that an application of a law of nature or mathematical formula to a known structure or process may well be deserving of patent protection.” Diehr, 450 U.S. at 187, 209 USPQ at 8 (emphasis in original).

“While a scientific truth, or the mathematical expression of it, is not a patentable invention, a novel and useful structure created with the aid of knowledge of scientific truth may be.” Diehr, 450 U.S. at 188, 209 USPQ at 8-9 (quoting Mackay, 306 U.S. at 94).

6. 1982, CAFC Formed.

————————————————————

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Court_of_Appeals_for_the_Federal_Circuit

7. 1994, Alappat (CAFC).

————————————————————

Two en banc decisions of the Federal Circuit have made clear that the USPTO is to interpret means plus function language according to 35 U.S.C. §112, sixth paragraph. In re Donaldson, 16 F.3d 1189, 1193, 29 USPQ2d 1845, 1848 (Fed. Cir. 1994) (in banc); In re Alappat, 33 F.3d 1526, 1540, 31 USPQ2d 1545, 1554 (Fed. Cir. 1994) (in banc).

The plain and unambiguous meaning of section 101 is that any new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may be patented if it meets the requirements for patentability set forth in Title 35, such as those found in sections 102, 103, and 112. The use of the expansive term “any” in section 101 represents Congress’s intent not to place any restrictions on the subject matter for which a patent may be obtained beyond those specifically recited in section 101 and the other parts of Title 35…. Thus, it is improper to read into section 101 limitations as to the subject matter that may be patented where the legislative history does not indicate that Congress clearly intended such limitations. Alappat, 33 F.3d at 1542, 31 USPQ2d at 1556.

8. 1998, State Street (CAFC) – Useful, Concrete, and Tangible Result.

————————————————————

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued opinions in State Street Bank & Trust Co. v. Signature Financial Group Inc., 149 F. 3d 1368, 47 USPQ2d 1596 (Fed. Cir. 1998) and AT&T Corp. v. Excel Communications, Inc., 172 F.3d 1352, 50 USPQ2d 1447 (Fed. Cir. 1999). These decisions explained that, to be eligible for patent protection, the claimed invention as a whole must accomplish a practical application. That is, it must produce a “useful, concrete and tangible result.” State Street, 149 F.3d at 1373-74, 47 USPQ2d at 160102.

9. 2010, Bilski (US Supreme Court).

————————————————————

Decided 06/28/10.

Erik J. Heels writes about technology, law, baseball, and rock ‘n’ roll. He is @ErikJHeels on Twitter and is a mere mortal.

See also:

* Guest Post: USPTO Must Amend Examiner Guidelines On Bilski

by Paul Craane of Marshall Gerstein & Borun

http://www.patentlyo.com/patent/2010/07/guest-post-uspto-must-amend-examiner-guidelines-on-bilski.html

I agree!!! Excellent explanation!!

Awesome post!

I’m a former software developer turned patent attorney. Many of my reactions to Bilski v. Kappos were similar to yours: exactly *why* is Bilski’s claim “abstract” ? why do we need the 3 exceptions, since I wouldn’t know how to go about claiming “a law of nature” or “an abstract idea”? and why do the Justices insist that we need 101 to solve problems that 102, 103, and 112 already handle just fine?

Your post crystallized a lot of my thoughts in a manner that is both concise and clear. Thanks.

By popular demand, I added a table of contents to:

* A Mere Mortal’s Guide To Patents Post-Bilski (Or Why §101 Is A Red Herring)

http://erikjheels.com/?p=2222