17 Seconds #61 – A Publication For Clients And Other VIPs Of Clocktower.

[Editor’s note: CAUTION, this newsletter, if printed, is about 70 pages long. If you are going to save it, then we suggest saving it electronically, not on paper.]

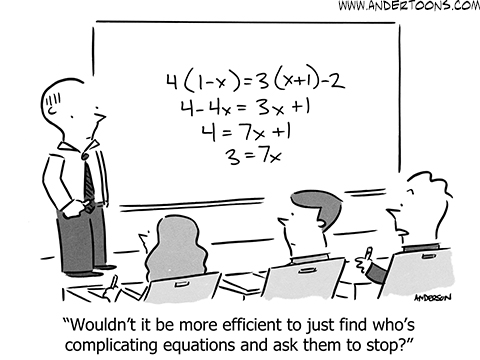

To slightly rephrase this cartoon, startups might ask “Wouldn’t it be more efficient to just find who’s complicating IP law and ask them to stop?”

Yes, it would be. But as long as IP law remains a messy mixture of constitutional law, statutory law, regulations, USPTO guidelines, and caselaw, you will need law firms like Clocktower to translate the legalese of IP law into plain English.

As I have written about previously, Clocktower has created a (MAMP-powered) library of paragraphs describing patent and trademark law in plain English. Each of said paragraphs is included in one or more email messages, each of which is most relevant at a particular point in time in the patent/trademark prosecution timeline.

The mother of all of these email messages, which includes all of the paragraphs (but not all of the email messages), is Clocktower’s “welcome letter,” so called because it used to be sent out on paper. I have often contemplated publishing an expanded version of the welcome letter as a book, but the problem with IP law these days is that it is changing faster than I could get a book to print!

So this newsletter will have to suffice.

There is a concept applicable to learning foreign languages and to marketing, namely the “seven times rule,” which states that a word (for language) or concept (for marketing) must be communicated seven times to stick. So we repeat ourselves a lot. It is intentional.

Without further ado, here is our “welcome letter,” in which we attempt to describe IP law in plain English, and which is as long as a book.

But feel free to contact your elected officials to ask them to stop complicating IP law!

—snip—

SUBJECT: Clocktower welcome & IP strategy

Hi TODO,

1. What’s Here

This email includes a detailed glossary of intellectual property (IP) law issues. Patent law is insanely complicated. Patent law is the only law practice specialty that requires both (1) a specific undergraduate degree (typically engineering) and (2) a separate bar exam (the so-called “patent bar” exam). Trademark law is also very complex. Both patent law and trademark law are administered by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). We have translated patent law, trademark law, and related IP law concepts into plain English. You will see these concepts in context during the course of filing, prosecuting, and renewing your patents and trademarks. Our job is to teach you enough about IP law to make the right business decision at the right time. Your job is to teach us enough about your business to write the patents and file the trademarks. The two most important concepts are as follows:

PATENT PLANNING – FILE BEFORE LAUNCHING. U.S. patent law changed significantly from 2011 to 2013 due to the America Invents Act (AIA) (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leahy-Smith_America_Invents_Act). The AIA was fully implemented on 2013-03-16, which made the U.S. a first-inventor-to-file country (and replaced the former first-to-invent system). The U.S. is also essentially an “absolute novelty” country. As such, you should file your patent application before you launch (where “launch” is defined as sale, offer for sale, publication, or public use) your product/service/improvement. This is the only certain way to protect both U.S. and foreign patent rights.

TRADEMARK PLANNING – FILE BEFORE LAUNCHING. It is much more expensive to cure trademark problems than it is to prevent them. As such, you should fully vet any new trademark (for a company name, logo, tagline, product name, service name) by searching the trademark and (if the search is favorable to you) filing a trademark application. We have guided many clients through the expensive rebranding process. In an ideal world, you would be the first to use, first to file, and first to register your trademark. Disputes with third parties can occur when one party is first at one thing and the other party is first at another. Registering your trademarks as soon as possible can also help you secure your brand on the Internet, including domain names and social networking usernames.

HOW WE COMMUNICATE. This is an example of how Clocktower communicates:

- All of our key emails and letters include three sections: (1) What’s Here, (2) Recommendation & Requested Action, and (3) Next Steps.

- We use descriptive subjects, including our docket information, so that emails are easier to search/find.

- We date documents in YYYY-MM-DD format so that sort-by-name equals sort-by-date.

- We CC info@clocktowerlaw.com on key emails (and ask you to do likewise) since email to that address goes to all of us in the firm.

- Many of our emails and letters (including this one) are based on templates that we are constantly updating. Your feedback and suggestions are welcome. Continuous improvement is our goal!

2. Recommendation & Requested Action

We recommend reading and saving this email. Please note all deadlines. We require notice two months before all patent deadlines and two weeks before all trademark deadlines to prepare and file the appropriate documents.

3. Next Steps

We will periodically send you letters and emails. For example, after your patent application is filed, we will send status reports every six months (in the fall and spring).

Thank you for choosing Clocktower. Let us know if you have any questions.

Best,

Mary

Best,

Mike

Best,

Erik

—

Clocktower Law LLC

537 Massachusetts Ave., Suite 301

Acton, MA 01720

http://www.clocktowerlaw.com

—snip—

Copyright Law

COPYRIGHTS VS. PATENTS VS. TRADEMARKS. Generally, your company’s name and logo can be trademarked; your company’s product can be patented, copyrighted, or both. Copyright protects against making exact copies, while patents provide broader protection, protecting against not only literal copying but also equivalent copying. Copyright registration is a matter of filling out the right forms and sending in the right fees, and all of the forms are online at the U.S. Copyright Office (http://www.copyright.gov/). As such, we have rarely done copyright work for our clients, not because we’re not good at it, but because we feel that it is money that is not well spent.

Domain Names

DOMAIN NAME DISPUTE – UNIFORM DISPUTE RESOLUTION POLICY (UDRP) OVERVIEW. The UDRP was established by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) to resolved disputes regarding the registration of domain names (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UDRP). For a complainant to acquire a domain name from a registration via a UDRP proceeding, the complainant would must show that:

(1) The domain name is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark or service mark in which the complainant has rights;

(2) The domain name registrant has no rights or legitimate interests in the domain name; and

(3) The domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith.

Proving bad faith is difficult. If a domain name contains only generic or descriptive words, then the complainant is not likely to prevail. If the domain name contains distinctive words, then the complainant is more likely to prevail. Evidence of bad faith includes – but is not limited to – unsolicited offers by the registrant to sell the domain name to the complainant.

FOREIGN DOMAIN NAMES. For list of top-level domain names, their meaning, their origin, and who may register them, see the Network Solutions website (https://www.networksolutions.com/faq/extension-whatis.jsp).

WHOIS INFO FOR CLOCKTOWER. If you use the same email address for all types of whois contacts, then you increase the risk of domain name theft. For this reason, we list Clocktower Law LLC as the administrative/billing contacts and GiantPeople LLC as the registrant/technical contacts.

organization/registrant/owner/client: Clocktower Law LLC | GiantPeople LLC

firstname: Erik J.

lastname: Heels

address1: 537 Massachusetts Ave., Suite 301

address2: [blank]

city: Acton

state: MA

ZIP: 01720

country: United States

email: info@clocktowerlaw.com | info@giantpeople.com

nameservers: NS29.DOMAINCONTROL.COM, NS30.DOMAINCONTROL.COM

Clocktower Policies

CLOCKTOWER CONFLICTS POLICY.

a. Clocktower Law LLC (Clocktower) conducts conflict-of-interest checks for each new client.

b. If there is an actual conflict of interest, then we are unable to represent either party, and we withdraw from (or decline to commence) representation.

c. If there is the appearance of a conflict of interest, then we will also withdraw from representation, unless both parties consent to the representation.

d. Clocktower never puts the interests of one client above another.

CLOCKTOWER DOCUMENT RETENTION POLICY. We save key documents as PDFs. We retain email metadata for one year, all other files for ten, after which we delete them. We backup all documents daily. We don’t maintain paper files.

CLOCKTOWER MISTAKES POLICY. No law firm is perfect. When we make a mistake, we will admit it, fix it as soon as possible, to the best of our ability, to the extent possible, and at no cost to you.

CLOCKTOWER TECHNOLOGY POLICY. We run the latest versions of Acrobat, FileMaker, and OpenOffice. For billing, we use QuickBooks Online. To ensure our technology is up to date, we replace computers every four years.

Patent Law

PATENT ARTICLES.

* The Who, What, Where, When, Why, And How Of Patents

http://www.clocktowerlaw.com/3112.html* Drawing That Explains Patent Costs

http://www.clocktowerlaw.com/3042.html

PATENT ASSIGNMENTS. In an application with multiple inventors, each inventor has the right to license the application. With an assignment to one company, this problem doesn’t exist. Plus, an assignment to a company is often required by any potential investors. In order for us to prepare the assignment documents, we need the name, home address, and citizenship of each inventor, and the name, address, and state of incorporation of your company.

PATENT BOOK – PATENT IT YOURSELF BY DAVID PRESSMAN. If you have the time but not the money to file patents, then there are still good options available to you. The book “Patent It Yourself” by David Pressman (https://store.nolo.com/products/patent-it-yourself-pat.html) is a good intro to the patent process in general.

DESIGN PATENT CLAIMS. “The claim shall be in formal terms to the ornamental design for the article (specifying name) as shown, or as shown and described. More than one claim is neither required nor permitted.” (37 CFR 1.153).

DESIGN PATENT DRAFTING. A design patent application has three primary parts: (1) a title, (2) a claim describing the design, and (3) one or more drawings. The title and the claim describe the the object to which your design relates. The title and design should be crafted broadly to cover all possible uses. The drawings for the design application should show as many views of the claimed design as are necessary to fully describe and disclose the design, because no new matter may be added after the application has been filed. Broken or dashed lines may be used to show portions of the object not pertinent to the claimed design. We recommend at least three views: (1) a top plan view, (2) a side plan view, and (3) a perspective view.

DESIGN PATENT DRAWINGS. “The design must be represented by a drawing that complies with the requirements of 37 CFR 1.84 and must contain a sufficient number of views to constitute a complete disclosure of the appearance of the design.” (37 CFR 1.152).

DESIGN PATENT INFRINGEMENT. Whether an accused product infringes a design patent is a matter of fact. To determine if a design patent is infringed, the trier of fact (judge or jury) compares the non-functional aspects of the patented design with the accused product. The trier of fact determines whether the patented design as a whole is substantially similar in appearance to the accused design. If, in the eye of the ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, the two designs are substantially the same, and if the resemblance is such as to deceive such an observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other, then the accused product infringes the patented design.

DESIGN PATENTS IN A NUTSHELL. Design patents cover the non-functional ornamental aspects of an object (such as the look of an Apple iPod or of Nike sneakers). The design must also be new and nonobvious. Design patents last 15 years (35 U.S.C. 173). A design patent application must be directed to an ornamental design for an object. The object must have some functional use. The design must be inseparable from the object and not merely surface ornamentation. Design and utility patents are each entitled to claim priority from each other. In short, design patents relate to external appearance rather than internal structure or function.

DESIGN PATENTS VS. UTILITY PATENTS. In general terms, a utility patent protects the way an article is used and works (35 U.S.C. 101), while a design patent protects the way an article looks (35 U.S.C. 171). The ornamental appearance for an article includes its shape/configuration or surface ornamentation applied to the article, or both. Both design and utility patents may be obtained on an article if the invention resides both in its utility and ornamental appearance (MPEP 1502.01).

PATENT DRAFT – HOW TO REVIEW. Each patent draft should be reviewed (1) for accuracy, (2) to make sure it is “enabling,” and (3) to make sure that the “best mode” has been disclosed. If corrections are required, then please provide corrections as replacement paragraphs.

PATENT DRAFTING – NUMERICAL RANGES OF VALUES. The general rule for numerical range limitations is that the claimed ranges are patentable only for the ranges that one skilled in the art would consider supported by, or within the scope of, the original disclosure.

PATENT DRAFTING – PATENTABILITY VS. PATENT BREADTH. Having more elements in your invention improves the invention’s patentability but decreases the patent breadth. Having different elements improves the invention’s patentability. Having fewer elements increases the patent breadth. Many inventors must change their designs to accommodate the competing needs of patentability and patent breadth.

PATENT FILING RECEIPT – OFFICIAL. We have received the official Filing Receipt from the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) for your patent application. The filing receipt serves as documentation that your application is on file at the USPTO and gives you approval to file for foreign patents. The filing receipt also serves as a reminder to file an Information Disclosure Statement (IDS) and an assignment for your application.

PATENT FILING RECEIPT – UNOFFICIAL. Since we filed this application electronically, we have already received an unofficial receipt. In three to eight weeks, we should receive the official filing receipt for this application.

FOREIGN PATENTS AND ABSOLUTE NOVELTY. You should keep your inventions a trade secret until a patent application that covers the invention is filed. Most countries follow the “first to file” rule and apply the “absolute novelty” rule. As such, any pre-filing disclosures can make it impossible to obtain patents outside of the U.S. Outside of the U.S., the basic “absolute novelty” test is that something is new “if it does not form part of the state of the art.” For example, in Europe, the state of the art includes all that has been “made available to the public by means of a written or oral description, by use, or in any other way, before the date of filing [or priority] of the European patent application” and also includes, to a limited extent, matters in co-pending conflicting European applications. For something to lack novelty, the public must have had possession [knowingly or not] of the teaching of the invention. This means, for example, that there is no on-sale bar in European law. Someone can use a process in a commercial context and – provided that the public cannot find out how the invention is exercised – it can still be patentable. For products sold to the public, the test is whether the product can be analyzed (reverse engineered) to reveal the invention – regardless of whether or not someone had the motivation to analyze. If a product has been used before filing, then it is less likely that protection for the product can be obtained. With client/server type products, where only part of the system may have been made available to the public, and part kept secret, it may still be possible to protect those parts that have not been made public and the details of the relationship between the public and non-public parts. In short, whenever any disclosure of an invention has been made before the U.S. patent filing, there is a risk of losing corresponding foreign patent rights.

FOREIGN DESIGN PATENTS. Foreign patent applications based on design patents must be filed within six months of your earliest filing date. Within six months of your earliest-filed U.S. application, you can file applications in individual foreign countries (but not under the PCT). Note that not all countries offer design patent protection.

PCT DEMAND – DEADLINES AND THE MAVERICK COUNTRIES. Demand filings used to be required in order to get the full benefit of the 30-month PCT pendency period, but PCT rule changes in 2002 extended the full benefit of the 30-month period (without having to file a Demand) in all but a handful of countries, and even if you don’t file a Demand in those countries, you can still get the full benefit of the 30-month pendency period by filing regional (e.g. EPO) patent applications that include those countries. In other words, with or without filing a Demand, a PCT application provides up to 30 months for applicants to make a decision on filing patent applications in individual countries or regional patent offices (e.g. EPO). If you plan to file directly in the “maverick” countries (Luxembourg, Tanzania, or Uganda) at 30 months, then you must file a Demand by the 19-months deadline. Otherwise your deadline to file directly in these countries is at 20 months. You can still get protection in these countries without filing a Demand if you choose to file regional patent applications at 30 months with the European Patent Office (EPO) (for Luxembourg), and the African Regional Industrial Property Organization (ARIPO) (for Tanzania and Uganda).

PCT DEMAND – REASONS NOT TO FILE. Currently, only about 10% of PCT applicants worldwide choose to file a Demand (largely due to the 30-month rule changes in 2002, before which the demand filing rate was much higher). Cost is the main reason why applicants choose not to file a Demand. Another reason is that the initial PCT filing fees cover a search report and an initial, non-binding opinion on patentability. This report and opinion can be used to make a decision about whether to proceed at the national stage, or to file amendments. This Written Opinion is supposed to arrive at month 16. Unfortunately, this report usually does not arrive until after the deadline for filing a Demand.

PCT DEMAND – REASONS TO FILE. Filing a Demand will give you (1) an opportunity to amend your application, (2) an opportunity to rebut the examiner’s findings in the Written Opinion, and (3) a preliminary, non-binding opinion on novelty, inventive step, and industrial applicability (i.e. whether your invention is new, non-obvious, and useful). The Demand does not give you an opinion on patentability according to the national laws of the elected countries, but this preliminary opinion is usually persuasive to many countries, especially countries with smaller patent offices. The biggest advantage to filing a demand is the opportunity to amend claims, description, or drawings before entering the national stage. If the application needs to be amended, then amending during the international stage means that the application as amended will be sent to designated countries during the national stage. Otherwise, an applicant may spend thousands of additional dollars in prosecution costs to amend through individual patent offices. Another advantage is the opportunity to “grease the skids” for the national stage. If you receive a favorable preliminary examination, then the accompanying report may be persuasive to many national patent offices. This means that many individual patent offices may allow your patent application without initial rejections to overcome. Such a scenario can potentially save thousands of dollars in prosecution costs and enable patents to issue faster. Filing a Demand provides an opportunity to enter into a dialogue with the examiner at the International Preliminary Examining Authority to influence the content of the International Preliminary Report on Oatentability.

PCT – DEMAND. A key business decision for PCT applicants occurs 19 months from the priority date. At this time, you can choose whether or not to file a Demand for International Preliminary Examination (AKA a “Demand”). Filing the Demand is optional. The Demand can provide you with an idea of what would happen during prosecution in individual countries. An International Preliminary Examination Report (IPER) that is favorable to the patent applicant can be persuasive for countries with smaller patent offices, but the IPER is not binding on any patent office. As a result, only about 10% of PCT applicants choose to file a Demand. Most applicants are simply looking to delay foreign prosecution costs.

PCT – INTERNATIONAL PRELIMINARY REPORT ON PATENTABILITY (IPRP). For PCT applications, international preliminary examination is carried out on the basis of the International Search Report (ISR) and the written opinion of the International Searching Authority and concludes with the International Preliminary Report on Patentability (IPRP). The purpose of the international preliminary examination is to formulate an opinion – which is preliminary – on whether the claimed invention appears (1) to be novel, (2) to involve an inventive step (i.e. nonobvious), and (3) to be industrially applicable (i.e. utility). While there is not a uniform approach to these criteria in national laws, their application under the PCT during the international preliminary examination procedure is such that the IPRP gives a good idea of the likely results in the regional/national phase. Note that although the IPRP is not binding on elected Offices, it carries weight with them (considerable weight with smaller patent offices), and a favorable report will assist the prosecution of the application before the elected Offices.

PCT – INTERNATIONAL SEARCH REPORT (ISR). About 16 months from a PCT application’s priority date, a PCT applicant will receive an ISR, citing patents and/or publications relevant to the patentability of your invention, and an accompanying Written Opinion. The ISR and Written Opinion can give you and idea about whether or not your application will be patentable. Responding to the ISR is optional, so there is no need to respond unless the cited references make amendments to the claims necessary. Claim amendments can also be made upon entering the national/regional phase.

The ISR (under PCT Article 18 and Rules 43 and 44) must be issued within three months of the date of receipt of the search copy by the International Searching Authority (ISA), or nine months from the priority date, whichever is later. An ISR contains:

- International Patent Classification (IPC) symbols;

- Indications of the technical areas searched;

- Indications relating to any finding of lack of unity of invention;

- A list of the relevant prior art documents; and

- Indications relating to any finding that a meaningful search could not be carried out with respect to certain (but not all) claims.

The Written Opinion:

- Is a preliminary non-binding opinion on novelty (i.e. not anticipated);

- Is a preliminary non-binding opinion on inventive step (i.e. not obvious);

- Is a preliminary non-binding opinion on industrial applicability (i.e. utility);

- Will be established for all PCT applications;

- Is sent to the applicant with the ISR;

- Is not published together with the application; and

- Has no formal procedure for applicants to respond (and applications should not respond informally, because your comments become public at the 30-month point).

PCT – NATIONAL/REGIONAL STAGE. Most industrialized countries are members of the PCT (http://www.wipo.int/pct/guide/en/gdvol1/annexes/annexa/ax_a.pdf), and WIPO has a good chart that illustrates the overall PCT process and timeline (http://www.wipo.int/pct/en/seminar/basic_1/timeline.pdf).

At the national stage (i.e. the 30-month point), you can file in individual countries or in groups of countries considered “jurisdictions.” For example, the European Patent Office (EPO) is considered a “jurisdiction” under PCT rules, so you could file one EPO application that would cover the major European countries (http://www.epo.org/about-us/foundation/member-states.html).

In most countries/jurisdictions, you have until the 30- or 31-month point to make a decision about filing foreign patent applications. There are three “maverick” countries (Luxembourg, Tanzania, and Uganda) that do not follow the 30- or 31-month rule. For these countries, you would need to begin foreign prosecution at 20 months. Coverage for these countries, however, can be recaptured at 30 or 31 months by filing regional patent applications. For example, to regain coverage in Luxembourg, you could file an EPO application by the 31-month deadline.

Filing in the EPO is expensive for U.S. residents. In addition to our having to work through a European agent, there are annual filing fees just for keeping your application pending at the EPO (http://www.epo.org/applying/forms-fees/fees.html). There are also annual filing fees for filing in some individual countries (e.g. France, Germany, Italy, Australia, the Netherlands).

FOREIGN UTILITY PATENTS. Foreign patent applications must be filed within one year of your earliest filing date. Whether your first-filed patent application was a provisional application or a non-provisional application, you have one year to file foreign patent applications based on your earliest-filed U.S. patent application. Within one year of your earliest-filed U.S. application, you can file applications in individual foreign countries (or jurisdictions such as the European Patent Office (EPO)) or you can file under the PCT.

A. Foreign Filing in Individual Countries

If you only want patent protection in a few countries and want protection as soon as possible, then it is best to file in each selected country. This immediately starts prosecution of your application on the merits in the selected countries and can result in patents issuing a year or more earlier than with the PCT.

Filing in individual countries involves two steps. First, file an application with the USPTO. Second, within 12 months of your U.S. filing, file individual applications in each country in which you want protection.

B. Foreign Filing under the PCT

If you believe that your invention will or may have economic value in multiple nations, then consider filing an application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT). By filing a PCT application, you can simultaneously seek protection for an invention in over one hundred countries (including the EPO).

Under the PCT, there is an initial cost to get the PCT application filed, and prosecution costs (when the application enters the “national stage”) about 12 months after filing. The PCT defers prosecution costs for individual countries until about 18 months after filing.

The PCT is a treaty regarding filing, searching, and examination of patent applications and the dissemination of the technical information contained therein. Although the PCT does not provide for the grant of “international patents,” the PCT provides many advantages:

- Single initial filing fee.

- Single preliminary international patent search.

- One set of formality requirements.

- Single international publication.

- Single international preliminary examination and prosecution of application.

- Translations and national fees required at 20 or 30 months and only if you wish to proceed.

A main advantage of filing a PCT application is the international search and preliminary examination of the application. PCT examiners check the application for international patentability, conduct an international patent search, and give a preliminary patentability opinion. You can review this patentability opinion before making a decision to proceed in individual countries. This patentability opinion is sent to the designated countries, which typically give weight to its findings but are not bound by the opinion.

You may either file first in the USPTO and then file under the PCT within 12 months, or you may directly file under the PCT. After filing under the PCT, you have 20 to 30 months from your earliest filing before prosecuting your application in each individual country. Thus, a PCT application buys you extra international “patent pending” time for your invention. In this way, a PCT application is like an extended, international, provisional application. The PCT is basically a fee-deferring device. It will not spare you from translation and prosecution costs in foreign countries, but it can postpone that decision for up to 30 months.

In short, if you want to protect your invention in other countries, then you will need to file foreign patent applications, an EPO application, or a PCT application before the one-year anniversary of your earliest patent filing (e.g. the provisional filing date if you filed a PPA).

PATENT FORMS. For the patent forms, we need home address, phone number, and citizenship information for all named inventors. You can fax the signed forms back to us. We recommend saving the signed originals.

PATENT HURDLE – NOVELTY AND ANTICIPATION. In order for an invention to be patentable, its elements must be novel. If any “prior art” (patent, patent application, or publication) includes all of your invention’s elements, then your invention has not satisfied the novelty requirement. In this case, the prior art is deemed to “anticipate” your invention (i.e. to render it “not novel” in the eyes of the USPTO). Note that both old and current patents can anticipate an invention and thereby make it unpatentable.

PATENT HURDLE – OBVIOUSNESS. In order for an invention to be patentable, its elements must be nonobvious. If two or more previous inventions can be combined to include all of your invention’s elements, then your invention has not satisfied the nonobviousness requirement. When the USPTO rejects an invention as being “obvious,” they are essentially saying that it may be new, but not quite “new enough.”

PATENT INVENTORSHIP AND DATE OF INVENTION. Patent inventorship is determined on a claim-by-claim basis based on one question: “Whose idea was this?” Since claims change over time, so too can inventorship. Before any pending patent issues, you must review the final claims and remove any inventor whose ideas did not make it into the final approved claims. Similarly, you must correct inventorship to add any inventor whose ideas do make it into the final approved claims (and file the appropriate assignments). Failure to correct inventorship can render the patent invalid. Also. “reduction to practice” relates to date of invention but (confusingly) not to inventorship. In other words, the one who conceived of the idea is the inventor, regardless of who reduced it to practice. This is why Steve Jobs is listed (correctly) as an inventor on so many Apple patents, most of which he clearly did not personally reduce to practice.

- Conception. “Unless a person contributes to the conception of the invention he [or she] is not an inventor…. One must contribute to the conception to be an inventor.” In re Hardee, 223 USPQ 1122, 1123 (Comm’r Pat. 1984). MPEP 2137.01.

- Reduction To Practice. “There is no requirement that the inventor be the one to reduce the invention to practice so long as the reduction to practice was done on the inventor’s behalf.” In re DeBaun, 687 F.2d 459, 463 (CCPA 1982).

- Joint Inventors. Inventors may apply for a patent jointly even though: (1) they did not physically work together or at the same time, (2) each did not make the same type or amount of contribution, or (3) each did not make a contribution to the subject matter of every claim of the patent. 35 UCS 116. “The critical question for joint conception is who conceived, as that term is used in the patent law, the subject matter of the claims at issue.” Ethicon, 135 F. 3d at 1460.

- Licensing. In the absence of any agreement to the contrary, each of the joint owners of a patent may make, use, offer to sell, or sell the patented invention within the United States, or import the patented invention into the United States. 35 USC 262.

- Identifying Inventors. Contributions of named inventors should be evaluated after claims defining the invention are finalized. Inventorship may vary from claim to claim. Claim amendments may impact inventorship. Try to get all team members to agree who are the inventors. Each inventor not have made an equal contribution to the invention.

PATENT ISSUANCE – CERTIFICATE OF CORRECTION. Please review your patent for any errors. Minor errors can be corrected by filing for a Certificate of Correction. Alternatively, minor errors may simply be made of record in the patent file through a letter. Correcting material errors would require reexamination of the patent. If there are any errors in the patent that you believe are worth correcting, then please contact us.

PATENT ISSUANCE. Patents generally issue six weeks after paying the issue fee. The issued patent will be published in the USPTO Patent Official Gazette, which is often read by potential licensors. The patent will be valid for twenty years from the date of originally filing the parent application.

PATENT ISSUED. Congratulations! The USPTO has issued a patent for the subject application. The original patent document is enclosed. The patent grants you the right to exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, or selling the invention throughout the U.S. or importing the invention into the U.S. for the term of the patent.

PATENT LICENSING. In some cases, you may need to secure a license to avoid infringement. In other cases, you may be able to generate revenue by licensing your invention to others. A patent, by itself, cannot infringe another patent. A prerequisite of infringement is that you must make, use, or sell the patented item in this country. In other words, even when you patent something, you must license others to be able to make, use, or sell your patented invention. Similarly, others must license your patent in order to make, use, or sell their products (whether patented or not).

PATENT MAINTENANCE FEES. Patent renewal fees (called “maintenance fees”) are due at 3.5, 7.5, and 11.5 years from the patent’s issue date. Failure to pay the maintenance fees on time may result in expiration of the patent. The USPTO does not mail notices to patent owners that maintenance fees are due.

PATENT NOTICE OF ALLOWANCE. When a Notice of Allowance issues, you have three months to pay the Issue Fee. If you don’t pay the Issue Fee, then the application will go abandoned.

OFFICE ACTION DELAYS. The Patent Office is supposed to provide a first Office Action within 14 months of the filing date (35 U.S.C. 154), but the average time for receiving a first Office Action can be substantially longer. If your Office Action is sent more than 14 months from the filing date of your application, then the term of your patent will be extended accordingly.

OFFICE ACTION FOUND ALLOWABLE SUBJECT MATTER – YOU’RE ABOUT TWO MONTHS FROM ONE PATENT. Very good news. In this Office Action, the examiner found some claims allowable, rejecting the rest. So we can split this application in two, pay the issue fee, and you’ll have at least one issued patent in about two months.

OFFICE ACTION REPLY. In order to overcome the USPTO’s rejections, we must craft a reply to the Office Action with legal arguments that technically distinguish your invention from the prior art. The key to this analysis is distinguishing how the elements of your invention (as defined in the claims) are different from the elements of the prior art. You can identify the technical differences (e.g. by creating a simple chart), and we can describe these differences with the proper legal language for the reply.

OFFICE ACTION – RESTRICTION REQUIREMENT. This Office Action is procedural, not substantive. The USPTO has stated that the application claims multiple distinct inventions. There are three options for responding: (1) argue that the restriction requirement was improper, (2) divide the application into multiple divisional applications (one for each species of invention), or (3) elect one species. Option 1 is usually not successful. Option 2 is expensive, because it results in multiple patents. The USPTO will gladly accept additional filing fees to search and examine what it considers to be multiple inventions, but you only get one search/examination for the filing fees that you’ve paid. As such, option 3 is what most applicants choose, sometimes in combination with option 1. In other words, the most common approach is to elect one species of invention while arguing that the restriction requirement was improper.

OFFICE ACTION. The USPTO’s reply to a patent application is called an “Office Action.” In the first Office Action, the USPTO initially examines the patentability of your invention. The USPTO typically rejects all of the claims in a patent application in its first Office Action, essentially challenging us to prove that your invention is patentable. In subsequent Office Actions, the USPTO may make similar arguments, which require more fine-tuned replies. You usually get only two Office Actions for your initial filing fee and can usually continue prosecution (i.e. beyond the second Office Action) by paying additional fees. It is not unusual to have two or more rejections from the USPTO.

PATENT OUTLINE – PUBLISHED APPLICATIONS. Here are some patent documents that are based on our patent outline:

* Network Monitoring, Detection, and Analysis System

Avraham Tzur Freedman, Ian Gerald Pye, Daniel P. Ellis (published 2017-07-20)

https://www.google.com/patents/US20170208077* Multi-User Cloud Parametric Feature-Based 3D CAD System

Jon K. Hirschtick et al. (published 2016-08-25)

https://www.google.com/patents/US20160246899* Method And System For Large Scale Data Curation

Nikolaus Bates-Haus et al. (published 2015-10-01)

https://www.google.com/patents/US20150278241* Numeric Input Control Through A Non-Linear Slider

Michael Lauer (published 2015-10-01)

https://www.google.com/patents/US20150277718* Switching Device Configured For Operation On A Conventional Railroad Track

Brendan English (published 2014-10-23)

https://www.google.com/patents/US20140311377* Optical Analyzer For Identification Of Materials Using Reflectance Spectroscopy

Ronald H. Micheels, Don J. Lee (published 2013-10-03)

http://www.google.com/patents/US20130256534* Yoga Mat With Intuitive Tactile Feedback For Visually Impaired

Tracy Lynn Curley (published 2011-05-19)

http://www.google.com/patents/US20110118097* Auto-Lock Compact Rope Descent Device

Peter M. Schwarzenbach, Samuel Morton (published 2010-09-23)

http://www.google.com/patents/US20100236863* Human-Computer Productivity Management System And Method

Mark Anthony Chroscielewski (published 2009-09-03)

http://www.google.com/patents/US20090222552* Online Entertainment Network For User-Contributed Content

Benjamin Clark Campbell (published 2008-04-17)

https://www.google.com/patents/US20080091509* System And Method For Optimizing Website Visitor Actions

Eric Hansen (published 2006-11-30)

http://www.google.com/patents/US20060271671* Method And System For Pricing Electronic Advertisements

Brian O’Kelley (published 2006-06-08)

http://www.google.com/patents/US20060122879* Pressure-Sensitive Light-Extracting Paper

Kevin Gerard Donahue (published 2006-05-18)

http://www.google.com/patents/US20060105149

PATENT OUTLINE. Our patent outline (clocktower-patent-outline.doc) helps keep your costs down by providing us the info that we need to write the patent. There are lots of instructions in the document itself.

[OPTION]

As discussed, you have decided to file a provisional application now. Since you are post-launch, foreign patents are not possible (but this matters less for software, which is difficult/impossible to patent out side of the US). Filing a provisional is a good choice for startups whose products are still evolving. The big picture plan is to file additional provisionals for any patentable improvements (if any). Then, within a year of the earliest provisional, file a single U.S> nonprovisional application that rolls up all previous provisionals.

[OPTION]

Don’t worry that the outline says “utility patent application” when we’re filing a “provisional patent application.” To write a good provisional patent application, we must write it as it if were a utility patent application.

PATENT-PENDING vs. ISSUED PATENTS. Your invention is “patent-pending” as soon as any type of patent application is filed (and as long as the application is not abandoned). “Patent-pending” primarily gives you bragging rights. Patent applications have no enforceable rights until a patent is granted. However, if an application owner puts a third party on notice about an application, and if the third party infringes claims of a patent application that eventually issues as a patent, then the third party could be responsible for a reasonable royalty for any products sold during the patent pendency. A reasonable royalty is not a significant judgment as most royalty rates are single digit percentages. After a patent is granted, a patent owner can stop others from making, using, or selling the patented invention via patent litigation or otherwise. Willfully infringing a patent can result in triple damages.

When someone claims “patent pending” status, it is impossible to know whether or not they filed a Provisional Patent Application or a Nonprovisional Patent Application. Provisionals last for only one year and are not published. Nonprovisionals are published 18 months after they are filed unless the applicant filed a non-publication request (which states, among other things, that the applicant has not filed and will not file foreign patents). When nonprovisonals are filed with nonpublication requests, the application will not be published unless/until it issues. To further complicate matters, applications are often filed in the name of the inventor, and if the inventor has not filed an assignment, then no record of the employer will be found at the USPTO. In short, it is difficult to discover meaningful information about a claimed “patent pending” status.

PATENT PLANNING – BEST PRACTICES. Our general advice for patents is that you should file in countries where you have significant business, partners, investors, or potential acquirers.

PATENT PLANNING – BUSINESS ISSUES. It is never possible to say with certainty whether an invention is patentable or whether an invention will infringe an existing patent. Ultimately, your decisions whether to pursue a patent and whether to make or use or sell your invention will be business decisions based on all factors, including any legal issues.

PATENT PLANNING – EQUINOX STATUS REPORTS. While your patent is pending and awaiting a response from the USPTO (an Office Action), we will send you status reports twice per year (once in the spring, once in the fall). This (1) allows us to make sure that the USPTO hasn’t lost or misplaced your application, (2) provides you with a rough date of when you can expect a reply from the USPTO, and (3) satisfies the applicant’s duty of diligence. Most applications are pending for multiple years before the USPTO begins to examine them.

PATENT PLANNING – FILE BEFORE LAUNCHING. U.S. patent law changed significantly from 2011 to 2013 due to the America Invents Act (AIA) (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leahy-Smith_America_Invents_Act). The AIA was fully implemented on 2013-03-16, which made the U.S. a first-inventor-to-file country (and replaced the former first-to-invent system). The U.S. is also essentially an “absolute novelty” country. As such, you should file your patent application before you launch (where “launch” is defined as sale, offer for sale, publication, or public use) your product/service/improvement. This is the only certain way to protect both U.S. and foreign patent rights.

PATENT PLANNING – INFRINGEMENT AND DESIGNING AROUND. In order for any invention to “infringe” a current patent, the invention must contain each element of the patent, or the invention must contain elements that perform substantially the same function in the same way to achieve the same result. This latter concept is known as the “Doctrine of Equivalents.” For example, if a current patent contains three elements (A+B+C), and your invention contains four elements (A+B+C+D), then your invention would infringe the patent. If you substituted element A2 for A, but element A2 performs the same function, in the same way, and achieves the same result as A, then your modified invention (A2+B+C) would still infringe the patent. However, if you remove one of the elements (removing A) from your invention (now B+C) or if you change one element (changing A to E) so that it performs a different function, performs in a different way, or achieves a different result, then your modified invention (B+C or E+B+C) would not infringe the patent. So one way to avoid infringing a patent is to “design around” the invention by either (1) eliminating an element or (2) changing the function, manner, or result of an element.

PATENT PLANNING – MARKING. When a patent is filed, your invention is “patent pending.” You can, and in most cases should, mark your invention as such. It is not necessary to include the patent application’s serial number with any “patent pending” notices. When your patent issues, you can, and in most cases should, mark your product and product literature with the patent number to put others on notice that your invention is patented.

PATENT PLANNING – ONE-PAGER.

If | And | Then |

|---|---|---|

you have |

| file patents |

you | you choose | you should keep |

you | you choose | you should keep |

you | you want | you have one-year |

you | you want to | you have one-year |

you | it is | re-read this |

PATENT PLANNING – COST FACTORS. The following factors impact the cost of your patent application:

- The complexity of the invention.

- Whether we conducted a formal patent search (lowers cost).

- Using our patent outline (lowers cost).

- Patent type – provisional vs. nonprovisional.

- How well attorney/client communicate electronically.

PATENT PLANNING – PRE-FILING SALES BY THE INVENTOR. The America Invents Act (AIA) went into effect in 2013, but not all aspects of the law have been worked out. Post-AIA, filing patents after a “launch” event introduces additional risk for the inventor. In particular, it is unclear whether pre-filing sales of a product by an inventor bar the inventor from getting a patent on the product. The USPTO currently says that they do not, but the courts have not yet spoken on this issue.

Post-AIA, being on-sale prior to filing an application is a bar to patenting. However, post-AIA also includes an “exception” that “disclosures” made by the inventor within one year prior to filing are not bars. This begs the question whether being on-sale is also considered a “disclosure” under the AIA. The USPTO includes an applicable section in their manual for examiners:

The AIA does not define the term “disclosure,” and AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a) does not use the term “disclosure.” AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(b)(1) and (b)(2), however, each state conditions under which a “disclosure” that otherwise falls within AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(1) or 102(a)(2) is not prior art under AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a)(1) or 102(a)(2). Thus, the Office is treating the term “disclosure” as a generic expression intended to encompass the documents and activities enumerated in AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(a) (i.e., being patented, described in a printed publication, in public use, on sale, or otherwise available to the public, or being described in a U.S. patent, U.S. patent application publication, or WIPO published application).

This clarifies that the USPTO’s current position is that being “on sale” is a “disclosure.” Thus, the USPTO will not cite (1) sale activities, (2) by the inventor (3) that occurred within one year of filing. However, this is not an issue that has yet been settled by the courts, so if a future court holding indicates that “on sale” is not a “disclosure,” then any patent (or pending application) for something which was on sale prior to application would be void.

In short, if you launch your product before filing a patent, then we will not be able to file U.S. or foreign patents on it. But if your product/improvement is still a secret, or if you have future product/improvement plans, then we may be able to help.

PATENT PLANNING – PATENT PRIMER.

A patent gives the inventor the right to exclude others from making, using, and selling that invention 20 years from when the patent was filed.

Patents are designed to protect products/services and improvements to those products/services. So the best time to think about filing patents is after you’ve come up with the idea and before you’ve launched the product/service (or improvement). The best way to think about what you can patent is to think about what you can sell or license and how that offering is better/faster/stronger than the competition.

It is easy to over-spend on intellectual property (patents, trademarks, domain names). What makes sense is to get IP protection in the countries where you do business, where you intend to do business, or where potential acquirers do business.

PATENT PLANNING – PRODUCT-BASED PATENTING. Using our product-based patenting approach, our overall goal is to explain to the USPTO how your product is better/faster/stronger than the competition using features/benefits that we define, both in the present (i.e. the “prior art” section) and in the future (i.e. the “other embodiments” section).

PATENT PLANNING – PRODUCT IMPROVEMENTS. Improvements should be considered new inventions. If you file a patent on an invention and later make improvements to the invention, then the improvements may be separately patentable as separate inventions. You should file patents on improvements before launching.

PATENT PLANNING – SOFTWARE PATENTS. Software can be patented, but the courts have not been making it easy:

- The 2007-04-30 KSR v. Teleflex Supreme Court decision made it easier for the USPTO to reject patents for being obvious (i.e. not new enough).

- The 2010-06-28 In re Bilski CAFC decision made it more difficult for companies to secure business method or software patents.

- After these cased, the USPTO published guidelines about how to apply these cases.

As a result of these cases and of the guidelines, we recommend that software-related patents be filed as provisionals, which gives you one extra year of patent pending and gives the law a chance to settle down. In light of KSR, if your invention consists of combinations of elements that exist in the prior art (either literally or equivalently), then we believe it will be extremely difficult – if not impossible – to secure a patent. Conversely, if your invention has the “nugget of newness” not found in the prior art, then it has a better chance of being patented. The bottom line is that software has been patentable for over a generation and remains patentable today.

PATENT PRELIMINARY AMENDMENT. Preliminary amendments can be used to defer the cost of writing a full set of claims. When employing this strategy, a preliminary amendment that includes a full claim set should be submitted within one year of the application’s filing date so that they will be examined.

PRIOR ART – DUTY TO DISCLOSE. Both the inventor(s) and their lawyer(s) have an ongoing duty to disclose information to the USPTO that is material to patentability as long as the patent application is pending (37 CFR 1.56, AKA Rule 56). All individuals covered by Rule 56 have a duty to disclose to the USPTO all material information they are aware of regardless of the source of or how they become aware of the information. A finding of ‘fraud,’ ‘inequitable conduct,’ or violation of duty of disclosure with respect to any claim in an application or patent, renders all the claims thereof unpatentable or invalid.

PRIOR ART – HOW TO SUMMARIZE. We must carefully define what the competition (i.e. the prior art found by the patent search) does and what they do not do. If you know of specific patents, patent applications, publications, or websites that we can reference, then those must be included. Imagine that the invention has been turned into a product and you are writing the marketing literature for your product. Compare the features, functions, and benefits of the product to those of the competitors. Pay particular attention to how the invention overcomes the limitations inherent in the competitors’ products. In other words, what problem(s) is the inventor trying to solve? Chronologically, how have others tried and failed to solve the same or similar problem(s)? How does the invention now solve the problem(s)? Cite any publications or patents that discuss the problem(s) the invention solves or previous failed attempts to solve the problem(s). Briefly discuss what the reference does and what it does not do. Don’t include opinions, only include facts. The prior art section of a patent application is very important, so don’t worry if it takes many pages to describe all of the prior art. For each piece of material prior art that we know about, we ask you to provide one paragraph, saying what each does, and what each does not do – without mentioning your own product.

PRIOR ART – INFORMATION DISCLOSURE STATEMENT (IDS) – NOT ALLOWED FOR PROVISIONALS. It is against USPTO rules to submit an Information Disclosure Statement (IDS), with material prior art, for provisional patent applications because they are not substantively examined. Any such IDS will be returned or destroyed at the option of the USPTO. MPEP 609.

PRIOR ART – INFORMATION DISCLOSURE STATEMENT (IDS). Each individual associated with the filing and prosecution of a patent application has a duty of candor and good faith when dealing with the U.S. Patent Office. This duty includes a duty to disclose all information known to each individual to be material to patentability of the claimed invention. This duty is deemed satisfied by filing an IDS. Although it is possible to satisfy this duty without filing an IDS, it is in your best interest to cite all material prior art, because when patents issue, the documents listed in the IDS are printed on the cover of the patent as “References Cited,” and there is a presumption that the patent’s claims are patentable over these references. If any person substantively involved in the filing and prosecution of the application becomes aware of additional information material to the patentability of the claimed invention, then that person has a duty to disclose this information to the USPTO to avoid loss of patent rights. This is a continuous duty that applies to each pending claim of the application.

[OPTION 1 – IDS HAS NOT BEEN FILED]

We typically file the IDS after receiving the Filing Receipt from the USPTO, so that information from the Filing Receipt can be included on the cover sheet of the IDS (which makes it less likely that the IDS will get lost at the USPTO).

[OPTION 2 – IDS HAS BEEN FILED]

We have filed the IDS with copies of all relevant patents and other prior art.

PATENT PUBLICATION AND PROVISIONAL RIGHTS. (1) If you mark your product/service “patent pending,” and (2) if one of those pending patent applications is published, and (3) if a competitor has “actual notice” of the published patent application, and (4) if it is later shown that the competitor infringed the as-issued patent, and (5) if the as-published claims are “substantially identical” to the as-patented claims, then the patent owner can get damages in the amount of reasonable royalty dating back to the date of publication. These financial rights in published patent publications are called “provisional rights” (not to be confused with a “provisional patent application”) and explain why some applicants choose to have their applications published. As you can see, it is a high bar to get over. The award of “provisional damages” depends on whether or not the defendant had “actual knowledge” of the published patent application. Such knowledge does not depend on marking your products/services “patent pending” but such marking can help establish such knowledge. Absent such knowledge, a patent owner can only get damages back to the date the patent issued. After patents have actually issued/granted, it does make sense to say something like “U.S. and foreign patents pending and issued, including patent numbers PATENT1, PATENT2, and PATENT3.” (where “PATENT1” and the like are the actual numbers of your patents).

PUBLICATION – NONPUBLICATION RESCISSION. Nonpublication requests must be rescinded within 45 days of a foreign or PCT filing to avoid the U.S. application being abandoned. Rescinding the nonpublication request means that your U.S. application will not remain secret, and it will be published approximately 18 months from its priority date. Unlike international applications, U.S. applications can be kept secret (by filing a nonpublication request with the initial filing) unless/until a patent is granted. Because international applications must be published at 18 months, an inventor can only keep a U.S. application secret as long as there is no related international application.

PUBLICATION – NONPUBLICATION TO BE RESCINDED. Since you have decided to file for foreign patents, your previously filed nonpublication request for your U.S. patent application must be rescinded. Failure to file the nonpublication request within 45 days will result in the U.S. patent application going abandoned. After the nonpublication rescission is filed, your U.S. patent application will be published approximately 18 months from its priority date. We will prepare and file the form to rescind the previous nonpublication request.

PATENT PUBLICATION VS. NONPUBLICATION. The USPTO publishes patent applications 18 months after they are filed. Applicants may avoid automatic publication by filing a nonpublication request.

A. Nonpublication

The advantage of nonpublication is that if a patent never issues, then the invention can be kept a trade secret. But note that if the launch of your product/service means that the “secret sauce” has been revealed or that the product/service can be reverse-engineered, then there is little value in trade secret protection. We usually recommend electing nonpublication, since you can easily rescind a nonpublication request, but preventing the publication of an application for which nonpublication has not been requested is very difficult and cannot be guaranteed. If a foreign or PCT application is filed based on your invention, then the nonpublication request must be rescinded within 45 days of the foreign filing to avoid the U.S. application going abandoned. If you are uncertain about whether a patent will issue on your invention or whether you will file for foreign patents, then you should elect nonpublication.

B. Publication

The advantage of publication is that potential infringers can be put on notice sooner, and unpatentable prior art disclosed in your patent application will become published prior art (which will make it easier for the USPTO to find, since the USPTO is better at searching patent prior art than non-patent prior art). If the as-published application is substantially the same as the as-issued patent, then you could, theoretically, get damages back to the date of actual notice. In practice, however, the as-published applications are rarely the same as the as-issued patents. If you are confident that you will receive a U.S. patent or if you immediately intend to file for foreign patents, then you should elect publication.

C. Publication And Foreign Patents Vs. Trade Secrets And US-Only Patents

If you file foreign patents, then your U.S. application will become published 18 months from its filing date. If a U.S. application is currently under a nonpublication request, then the nonpublication request must be rescinded if you file foreign. So you can keep your pending patent application a secret (unless/until a patent issues) only by choosing a US-only patent strategy (i.e. no foreign filing).

D. Our Default Is Nonpublication

In short, unless directed otherwise, we file nonpublication requests for all U.S. nonprovisional patent applications. If a foreign patent application (or PCT application) is filed within a year of a patent application priority date, then we will rescind the nonpublication request to prevent the U.S. application from going abandoned, and the U.S. application will be published 18 months from its priority date.

PATENT SEARCH – STUFF YOU CANNOT FIND. A patent search cannot find provisional patent applications (which are not published), design patent applications (which are not published), utility patent applications with a filing date less than 18 months old (since utility patent applications are published 18 months from their oldest priority date), and any patent application under a nonpublication request. So a patent search cannot find everything. But you can find what you can find, and you should find what you can find. It is good and proper due diligence for startups to do a solid patent search. Like the bear that went over the mountain, you should see what you can see.

PATENT SEARCH – FORMAL VS. INFORMAL. A “formal search” is conducted by a third-party search firm and includes information that is not available via the USPTO’s website. An “informal search” is conducted by anyone using information that is available via the USPTO’s website. The USPTO’s website does not allow you access to everything that you’d need for a formal search, but it can be very helpful. Inventors who are in the early stages of thinking about patents can benefit from a formal search. If a patent (or patent application) that is exactly like your invention is found, then you can save a lot of time and money. If, on the other hand, nothing like your invention is found, then you may be interested in proceeding with your patent application.

PATENT SEARCH – HALF-LIFE. A patent search has a relatively short half-life. In other words, the longer you wait between the patent search and the patent filing, the less valuable the patent search is. Our goal is to get patents filed one month after your decision to file. So if you do intend to file, then please let us know so that we can maximize the value of the patent search to your patent application.

PATENT SEARCH – NOT AN OPINION LETTER. This is not a noninfringement opinion letter, invalidity opinion letter, or freedom-to-operate opinion letter (also called “clearance opinion letter”). In order to write an opinion letter, a much more detailed examination of each patent must be made. Specifically, a patent attorney (typically at a patent litigator) must analyze the “file wrapper” of each patent. (See Underwater Devices, 717 F.2d at 1390.) The “file wrapper” includes all of the correspondence between the inventor and the USPTO and provides essential clues about the scope of the patent in question. Inventors generally seek opinion letters only when a patent owner has accused them of infringement or when they have discovered a patent that they want to avoid. These types of opinion letters take a long time to prepare and can cost tens of thousands of dollars. As such, a patent search is not an opinion letter. It is only an analysis of whether the invention that is the subject of the patent search can be patented in light of the prior art.

PATENT SEARCH – TO SEARCH OR NOT TO SEARCH. Under U.S. law, there is a duty to disclose to the USPTO any prior art (including patents, publications, and other inventions) that is material to the patentability of your invention, but there is no affirmative duty to search for this prior art. As such, many large law firms discourage inventors from conducting a patent search. Their theory is that the less you disclose to the USPTO, the more likely it is that your patent will issue. While this may be true, it does an inventor little good to get a patent by pretending that prior art doesn’t exist.

On the other hand, there are many good reasons to conduct a patent search:

- If the search reveals prior art that is exactly like your invention, then your business can save a lot of time and money by not filing a patent application or by not pursuing the underlying product/service all.

- In our experience, the USPTO will take your patent application more seriously if you disclose patent and non-patent prior art. We have seen applications that fail to disclose prior art get the slow treatment at the USPTO.

- A patent that discloses prior art typically ends up being a strong patent, because when the patent issues, the cover of the patent includes “References Cited,” and there is a presumption that the patent’s claims are patentable over these references.

- A patent search helps us navigate the landmine of prior art, and navigating the prior art is the key to writing strong patents.

- Searching has a good ROI for startups (with one/two pieces of IP on which to hang their hats) but necessarily a good ROI for big companies, which files thousands of patents/year, times thousands of dollars/search, equals millions of dollars/year. Most “expert” advice on patent searching is targeted at these big companies, not at startups.

- Patent applications that we search issue at 2.5 times the rate of those that we do not search.

For all of these reasons, we conduct a formal patent search for every patent application.

PATENT SEARCH – SCOPE OF REVIEW. When we review prior art from a patent search, we are looking for two things. First, we want to determine if any patent (old or current) “anticipates” your invention, which could make your invention unpatentable. Second, we want to determine if your invention is within the legal scope of any current patent, which could make your invention infringe one or more patents.

PATENT SEARCH – SUMMARY. A patent search rarely turns up something that is exactly like the invention in question. Inventions, however, are defined by their elements. You can almost always design around prior patents by adding or changing elements in your invention, but doing so could result in a patent for your invention with a narrow scope of protection.

PATENT SPECIFICATION – “BEST MODE” REQUIREMENT. The “best mode” requirement means that you must disclose the preferred embodiment of the invention. For example, for software inventions, you may disclose many embodiments of the invention using a combination of programming languages and hardware platforms, but if you prefer a particular programming language, operating system, and/or computer hardware, then this must be disclosed.

PATENT SPECIFICATION – DRAWINGS. Drawings need to be at most 6″ wide by 8″ tall. Also, there should be no shading or grayscale, only black and white. Patent drawings, when possible, should not contain any English text. If patent documents contain text elements, then they will must be translated into foreign languages for any foreign patents that are based on the U.S. patent application. We generally rely on the inventor(s) to supply the drawings. Otherwise, we can have our patent drawing colleagues prepare the drawings based on your drafts.

PATENT SPECIFICATION – “ENABLING” REQUIREMENT. The “enabling” requirement means that you must disclose enough of the invention to enable someone skilled in the art to make and use the invention. For example, for software inventions, flow charts and state diagrams would enable a programmer to recreate a program, but it is not necessary to disclose source code.

PATENT SPECIFICATION – OTHER EMBODIMENTS. In order to increase the scope of your patent, we ask that you look into the future and tell us what your product looks like five years from now. We willl then include one paragraph about each of these future developments – except that we will write in the present tense.

PATENT SPECIFICATION – TEACHING. The “specification” portion of the application (i.e. everything except the claims) must clearly teach one normally skilled in the field of your invention how to make and use the invention, and, if it has multiple modes or versions, then it must disclose the best mode or version of the invention (i.e. the version that the inventor prefers).

PATENT TYPES – CONTINUATION PATENT APPLICATIONS. While the application is still pending, you can file a continuation application on any new claims that you choose to present. No new matter can be added to a continuation application, only the claims differ. The filing and priority dates of the continuation application are (generally) the same as the earlier-filed parent application. If you want to file a continuation application, then you must do so before paying the issue fee.

PATENT TYPES – CONTINUATION-IN-PART (CIP) PATENT APPLICATIONS. While the application is still pending (i.e. before you pay the Issue Fee), you can file a Continuation-In-Part (CIP) application. Unlike divisional applications, new matter can be added to CIP applications, which are typically used for improvements that have been made since the initial filing. An advantage of CIPs is that they enables you to overcome publications that came out after the initial filing date. A disadvantage of CIPs is that the twenty-year patent term starts with the original filing date, not the filing date of the CIP. Matter common to the CIP and the parent application will (generally) have the filing and priority date of the parent application. New matter will have the priority and filing dates of when the CIP is filed.

PATENT TYPES. There are several types of patents. These are the most common:

- Design patents are for products whose design is the thing that is unique.

- Provisional patent applications last for one year and are like filing an extension on your taxes. Provisionals are not examined by the USPTO.

- Utility (or nonprovisional) patent applications are “regular” patent applications. Nonprovisional patent applications are examined by the USPTO. It typically takes multiple years after filing for the USPTO to examine and respond to patent applications. The responses are called “Office Actions.” You get two rounds of examination (i.e. two Office Sctions) for your filing fee. You can always pay more fees to the USPTO to get more rounds of examination. Examiners get points for disposing of patent applications, where “disposing of” means either (1) allowing the patent or (2) getting the applicant to abandon the application. We always try to make it more attractive to the examiner to choose path #1.

- Foreign patents come in many flavors. The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) is a centralized way of filing patents in multiple countries. Think of the PCT as a way of buying more time (like a provisional application) internationally. The most common route our clients to take to file foreign patents is as follows:

- File a patent application in the U.S.

- Within one year of the first U.S. application, file a PCT application.

- Within 30 months of the first U.S. application, file in the European Patent Office (EPO) based on the PCT.

PATENT TYPES – DIVISIONAL PATENT APPLICATIONS. While the application is still pending, you can file a divisional application on any claims that you opted not to prosecute due to an earlier restriction requirement. No new matter can be added to a divisional application, only the claims differ. The filing and priority dates of the divisional application are (generally) the same as the earlier-filed parent application. The justification for the divisional application is that the USPTO is obligated to examine only one invention per application (and filing fee). If you want to file divisional applications (including any divisionals for possible design patents), then you must do so before paying the issue fee.

PROVISIONAL PATENT APPLICATIONS – ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES. While it is true that a provisional patent application need not include all of the formalities of a nonprovisional application, a nonprovisional application that claims the benefit of a provisional’s earlier filing date can only do so to the extent that the provisional discloses and supports the as-claimed invention. As such, strong provisionals are written to look and feel exactly like nonprovisional applications so that the only thing a patent attorney needs to is write the claims. You can still file a nonprovisional application that claims priority to any provisional application, but with a weak provisional as the foundation, there will likely new matter that must be added to the nonprovisional application. If the new matter is not disclosed in the provisional application, then the new matter will only get the benefit of the later filing date, which defeats the purpose of having filed the provisional application in the first place.

Provisional patent applications – especially when filed pro se – can falsely raise expectations about cost savings and scope of protection. If you file a provisional application, then it needs to be considered the foundation upon which all future patent applications will be based. If the foundation is weak, then the follow-on applications will also be weak. The savings that might have been realized by filing a quick-and-dirty provisional application are lost when a patent attorney must rewrite everything and start from scratch.

It takes the same amount of work to properly draft a specification for a provisional patent application as it does for a nonprovisional patent application. Provisional patent applications always require a second patent filing within a year to keep your invention “patent pending,” delay examination (provisional patent applications are not examined by the USPTO), and ultimately end up costing more than simply filing a nonprovisional patent application. Alternately, we can file a nonprovisional patent application with one broad claim, and then within a year we can file a preliminary amendment to add additional claims. This approach combines the cost benefit of a provisional patent application with the prosecution speed of a nonprovisional patent application.

PATENT TYPES – PROVISIONAL PATENT APPLICATIONS. Nonprovisional patent applications must be filed within one year of provisional patent applications. When a Provisional Patent Application (PPA) is filed, you have “patent pending” status for your invention, but the PPA filing date starts a one-year period within which you must act to preserve the advantages of the PPA filing date. In short, if you want to keep your invention “patent pending” beyond the one-year anniversary of your PPA, then you will need to file a nonprovisional patent application within one year of your PPA’s filing date.

Trademark Law

TRADEMARK ARTICLES.

* The Who, What, Where, When, Why, And How Of Trademarks

http://www.clocktowerlaw.com/3133.html* Just Say Moo – How To Name And Brand Your Product To Make It Stand Out From The Crowd

http://www.clocktowerlaw.com/3016.html

TRADEMARK DECLARATIONS. With each filing, the Applicant declares the following: “The undersigned, being hereby warned that willful false statements and the like so made are punishable by fine or imprisonment, or both, under 18 U.S.C. Section 1001, and that such willful false statements, and the like, may jeopardize the validity of the application or any resulting registration, declares that: (1) he/she is properly authorized to execute this application on behalf of the applicant; (2) he/she believes the applicant to be the owner of the trademark/service mark sought to be registered, or, if the application is being filed under 15 U.S.C. Section 1051(b), he/she believes applicant to be entitled to use such mark in commerce; (3) to the best of his/her knowledge and belief no other person, firm, corporation, or association has the right to use the mark in commerce, either in the identical form thereof or in such near resemblance thereto as to be likely, when used on or in connection with the goods/services of such other person, to cause confusion, or to cause mistake, or to deceive; and that all statements made of his/her own knowledge are true; and that all statements made on information and belief are believed to be true.”

TRADEMARK DISPUTE – APPLICATION – EXPRESS ABANDONMENT. The USPTO allows a trademark applicant to “withdraw” a trademark application by filing an “Express Abandonment.” Such filings are typically made as part of settling a dispute with a third party. Abandoning a trademark application does not mean, however, that you have abandoned the trademark itself. It simply means that you are no longer pursuing registered status for the trademark with the USPTO. If it makes sense, then you can file another trademark application for the same trademark in the future.